Glacier systems in the Pamir and Tien Shan ranges are retreating rapidly; projections indicate over 50 per cent of glacier volume could be lost by 2100. This cryosphere meltdown is disrupting water cycles, threatening the livelihoods and food security of over 340 million people across nine countries. Without urgent intervention, communities risk worsening poverty, displacement, and instability.

The Glaciers to Farms (G2F) Programme responds to this crisis by integrating climate science into development planning and deploying concrete adaptation measures in glacier-dependent river basins. The programme focuses 100 per cent on adaptation and aligns with national priorities, including National Adaptation Plans (NAP), Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Excessive heat harms young children’s development, study suggests

Climate change—including high temperatures and heat waves—has been shown to pose serious risks to the environment, food systems, and human health, but new research finds that it may also lead to delays in early childhood development.

Published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, the study found that children exposed to higher-than-usual temperatures—specifically, average maximum temperatures above 86 °F (30 °C)—were less likely to meet developmental milestones for literacy and numeracy, relative to children living in areas with lower temperatures.

Warm oceans seem to be turning even ‘weak’ cyclones into deadly rainmakers

The final week of November was devastating for several South Asian countries. Communities in Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Thailand were inundated as Cyclones Ditwah and Senyar unleashed days of relentless rain. Millions were affected, more than 1,500 people lost their lives, hundreds are still missing, and damages ran into multiple millions of US dollars. Sri Lanka’s president even described it as the most challenging natural disaster the island has ever seen.

Primed to burn: what’s behind the intense, sudden fires burning across New South Wales and Tasmania

Since the megafires of the 2019–20 summer, Australia has had multiple wet years. Vegetation has regrown strongly. In recent months, below-average rainfall has dried out many landscapes, resulting in dry fuels ready to burn. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has warned these fires point to a “difficult” season ahead.

Do these fires mean Australia is facing another terrible fire season? Not necessarily. The growth of fuel is one thing. But a lot depends on the weather.

Five ways cities across Europe and Central Asia are adapting to extreme heat

Extreme heat is now one of the most urgent and fastest-growing climate risks across Europe and Central Asia. The summer of 2024 was the hottest ever recorded in Europe, while Central Asian cities are experiencing rising average temperatures, more frequent heatwaves and mounting stress on water, energy and health systems. Heat already causes more deaths than any other weather-related hazard, and urban growth is amplifying the risks.

Yet cities across the region are demonstrating that with the right tools, partnerships and planning, meaningful progress is possible.

Estimating Economic Resilience to Climate Impacts: The Gross Resilience Product

Climate impacts are reshaping economic realities across Africa. To understand what this means for future growth, the GCA Resilient Economies Index introduces an important new measure: the Gross Resilience Product (GRP). GRP identifies the share of a country’s GDP that remains resilient under projected climate impacts—offering a clearer picture of how climate hazards influence long-term development trajectories. Built using the Green Economy Model (GEM), it provides a quantitative, comparable estimate of climate-related risks to national economies.

From vulnerability to value: The economic payoff of adaptation in small island states

The economies and livelihoods of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to their geographic characteristics and economic structure, often dependent on tourism and trade. Critical infrastructure in SIDS is typically located near coasts or in areas at high risk of climate impacts. Countries such as the Maldives, with low-lying areas and roads, and hotels located in hazardous zones; and the Marshall Islands, which is at risk of being submerged due to rising sea levels, illustrate how SIDS are at risk of large economic damage from climate impacts.

Macroeconomic models can help create a clearer picture of the long-term implications of climate change and how adaptation action has the potential to create economic stability in SIDS.

Climate change and food prices

Food and climate change are closely linked. Food systems account for about one-quarter of all heat-trapping pollution. Meanwhile, extreme events fueled by climate change can damage crops, reduce yields, and disrupt supply chains — all of which can drive food prices higher. The availability, quality, and affordability of food reflect a complex set of climatic and socioeconomic factors. A recent study suggests that projected warming by 2035 would drive food price inflation in North America up by 1.4 to 1.8 percentage-points per-year on average. There are also examples of short-term price spikes in coffee, cocoa, California vegetables, and Florida oranges following exceptional heat, drought, and heavy rainfall in recent years.

Financing adaptation: 11 financial instruments that help build climate resilience

Climate adaptation has emerged as a high-return investment opportunity. A recent WRI analysis found that adaptation and resilience investments can unlock broad economic, social and environmental benefits that go far beyond simply avoiding losses, even when an extreme event doesn’t occur. The study — which evaluates the expected public benefits of 320 adaptation and resilience investments across agriculture, health, infrastructure and water — found that, on average, $1 invested in adaptation and resilience has the potential to generate more than $10 in benefits over 10 years.

Extreme Heat: The emerging science and its implications for Asia and the Pacific

This paper examines the potential for unprecedented heat events now and into the future and looks at how heat forecasting capabilities are evolving. It considers the compound effects when extreme heat combines with other hazards, and the socioeconomic and sector impacts of increased frequency and scale of extreme heat. The paper highlights how policymakers in Asia and the Pacific can harness this new knowledge to protect people from extreme heat using improved risk tools and warning systems, and heat-resilient public services and infrastructure.

Towards climate and extreme heat resilience: Lessons from African and Asian communities

The latest issue of Southasiadisasters.net brings together powerful insights from Africa and Asia on how communities are confronting climate change and extreme heat. From informal workers adapting to rising temperatures and girls’ education strengthening long-term resilience, to community-led early warnings in Tajikistan, agroforestry in Ghana, and heat-safe urban practices in India, the issue showcases practical, scalable solutions emerging from the ground up. Featuring contributions from 16 authors across the region, it highlights one message clearly: communities are not waiting—they are innovating, adapting, and leading the way toward a more climate-resilient future.

Mapping the impact and informing economic resilience

In response, this joint publication by the WMO and the UNDP presents a sectoral analysis of 91 weather, climate, and water-related Post-Disaster Needs Assessments (PDNAs) conducted between 2000 and 2024. The report highlights the socioeconomic impacts of hydrometeorological hazards, with recurring patterns of losses and damages observed in key sectors such as agriculture, housing, and transport. These sectors face both direct physical destruction and long-term disruptions to services, supply chains, and livelihoods.

The findings emphasize the need to move beyond reactive disaster response toward proactive, risk-informed development. Strengthening early warning systems, integrating National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, and improving access to standardized hazard-impact data are essential for effective preparedness and resilience investments.

The report finds that investing in a stable climate, healthy nature and land, and a pollution-free planet can deliver trillions of dollars each year in additional global GDP, avoid millions of deaths, and lift hundreds of millions of people out of hunger and poverty in the coming decades.

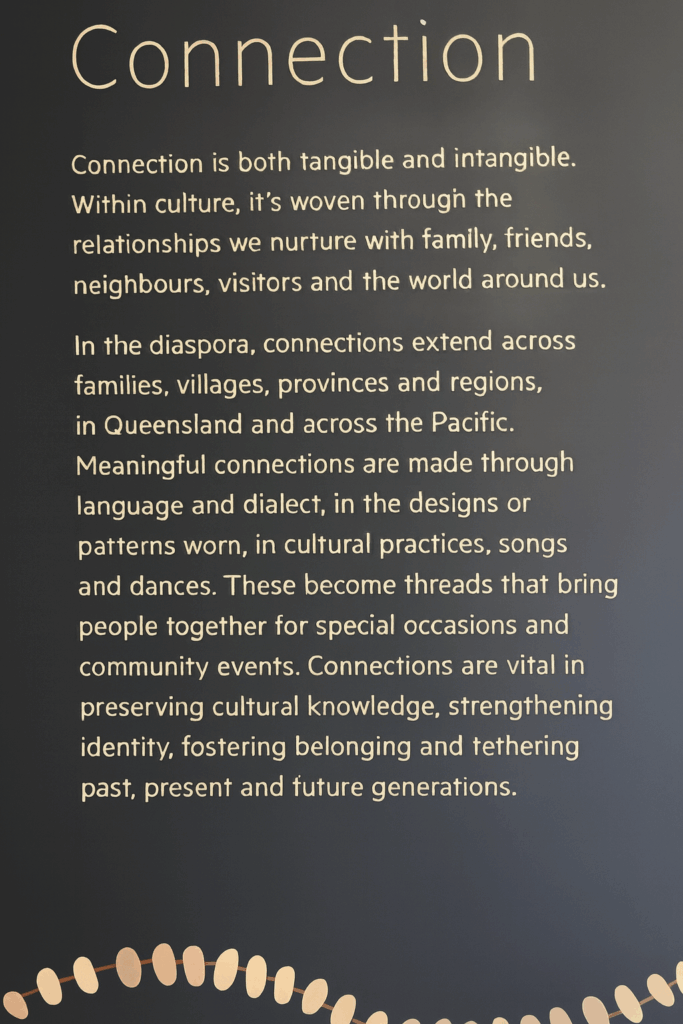

Following current development pathways will bring catastrophic climate change, devastation to nature and biodiversity, debilitating land degradation and desertification, and lingering deadly pollution – all at a huge cost to people, planet and economies. Instead, the world can follow another, better path laid out in the report. This involves whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches to transform the systems of economy and finance, materials and waste, energy, food and the environment – all backed by behavioural, social and cultural shifts that include respect for Indigenous Knowledge and Local Knowledge.

While there are up-front costs, the economic cost of inaction is much higher and the long-term return on investment of transformation is clear: the global macroeconomic benefits start to appear around 2050, grow to US$20 trillion per year by 2070 and rise thereafter.

This paper depicts several limits of conventional wildfire risk management measures towards Extreme wildfire events (EWEs) and introduces the concept of disaster risk management tipping points (DRM TPs) as critical thresholds that necessitate a revised set of disaster risk management strategies. Recent research shows that the number of extreme fire events is increasing exponentially and events such as the most recent fires in Los Angeles in the U.S. (2025), the Hawaii fires (2023), Canada’s record-breaking fires (2023), the largest recorded fires in Greece-Europe (2023) and the 2025 European fire season underpin this observation.

Building on a bibliographic review, the authors depict the novelty of the concept and apply it to selected illustrative examples. They propose that this conceptualisation is useful when developing “layered” or diversified risk management approaches for different types of wildfire events including extremes. It may also leverage and shift the discussion around responsibilities in managing risk in terms of public versus individual contributions, the distribution of investments as well as related aspects of justice.

Highlights from the extreme heat and agriculture report

Extreme heat is one of the central, interconnected drivers of the climate crisis in agriculture. It threatens global food security and the livelihoods of billions. More than an independent hazard, it acts as a powerful risk multiplier, amplifying drought and triggering wildfires, leading to compound negative outcomes for crops, livestock, fisheries and aquaculture, and forests. These impacts directly endanger the health and productivity of agricultural workers, who are on the frontlines of this crisis. Effective adaptation opportunities exist, particularly through the use of predictable heat forecasts to enable effective risk management. However, these actions must be supported by interdisciplinary research and integrated risk governance. Building resilience is imperative, but ultimately there are profound limits to adaptation.

Severe floods significantly reduce global rice yields

This paper’s findings highlight the need for flood-resistant rice cultivars to mitigate risks and support global food security, and implement adaptation strategies against both flood and drought rice yield losses. Research suggests that as climate change accelerates, intensifying extreme weather events, the stability of future rice production is at considerable risk.

Although rice is a semi-aquatic crop that benefits from controlled inundation—such as irrigation or shallow flooding during early growth stages—uncontrolled or severe flood events can substantially reduce yields. Globally, the increasing frequency of climate-related disasters, such as droughts and floods, has placed substantial pressure on rice yields, historically leading to famine, supply shortages, and regional price volatility.

Climate finance landscape in arid and semi-arid counties of Kenya

The report identifies several opportunities and innovative approaches for enhancing climate finance in the arid and semi-arid counties, including leveraging international support, strengthening local institutions, promoting sustainable investment models, and adopting nature-based solutions. Recommendations are provided to address challenges hindering effective mobilization and utilization of climate finance, such as limited access to financial resources, weak institutional capacity, fragmented coordination, and uncertain policy environments.

Science House – World Economic Forum, Davos

Science House is a new global space putting transformative science at the center of the conversation, spotlighting innovations and solutions that will shape healthy lives on a healthy planet. Nobel laureates, pioneering researchers, policy-makers, business leaders, and philanthropists will convene for high-energy debates, showcases, and strategic roundtables.

The purpose? Translating discovery into lasting impact beyond Davos. Championing open science and fostering collaboration across disciplines and sectors, Science House is the platform where scientific knowledge can inform decisions that define the future.

This webinar will translate the ECOWAS Directorate of Humanitarian and Social Affairs (DHSA)–UNDRR partnership under the ECHO-funded project into action by operationalizing regional cooperation mechanisms that reinforce ECOWAS’s mandate for coordinated disaster response. It will engage stakeholders across government, civil society, academia, and communities to ensure inclusive and sustainable preparedness frameworks, while leveraging international expertise from the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM), Copernicus Emergency Management Services, and the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) to strengthen West Africa’s disaster resilience.

Date: 16 December 2025; Time: 10:00-14:00 GMT

The training workshop aims to enable RCC and NMHS experts to provide high-quality climate services using state-of-the-art methodologies and tools. The workshop will comprise practical, hands-on and interactive sessions, including expert-led presentations on relevant tools and WMO approaches.

Date: 26 January 2026, 19:00 – 31 January 2026, 03:00: UTC: 26 January 2026, 06:00 – 30 January 2026, 14:00)

WCRP – Climate and cryosphere: open science conference 2026

The World Climate Research Programme is pleased to announce that the Climate and Cryosphere – Open Science Conference (CliC) will take place in Wellington, New Zealand from 9-12 February 2026.

The conference will include a diverse and cross-discipline town hall meeting, providing space for the international and interdisciplinary cryospheric community to make connections, discuss needs, find synergies, and plan meaningful action.

Marking 30 years of CliC, the Climate and Cryosphere Open Science Conference will contribute to the UN Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences (2025-2034) and prepare the community for the 5th International Polar Year (2032-2033).

Co-organized by the

Co-organized by the  infrastructures can promote science and innovation in line with the SDGs.

infrastructures can promote science and innovation in line with the SDGs.