At IDW2025, a group of speakers from around the globe gathered to address a long-standing problem: although data is the common currency of both research data management and data science, the two communities often work in parallel worlds—each with its own conferences, training pipelines, infrastructures, and priorities. As Christine Kirkpatrick noted in her opening remarks, this separation persists despite converging challenges around stewardship, reproducibility, education, and ethics. She framed the session as an invitation to rethink how these domains might come together.

At IDW2025, a group of speakers from around the globe gathered to address a long-standing problem: although data is the common currency of both research data management and data science, the two communities often work in parallel worlds—each with its own conferences, training pipelines, infrastructures, and priorities. As Christine Kirkpatrick noted in her opening remarks, this separation persists despite converging challenges around stewardship, reproducibility, education, and ethics. She framed the session as an invitation to rethink how these domains might come together.

What followed was a set of short talks revealing just how interdependent—yet disconnected—these communities have become, and how much potential lies in more intentional collaboration.

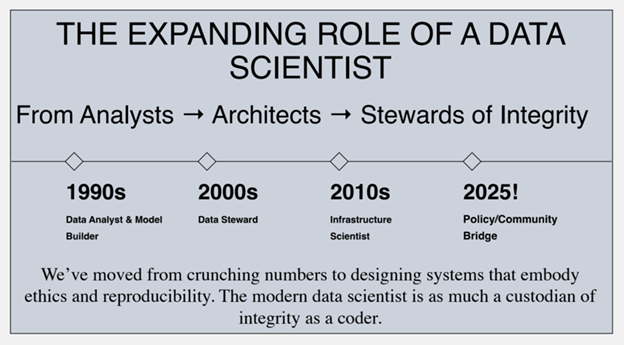

From Observation to Interpretation: A Research Lifecycle View (Leo Lahti)

Leo Lahti opened with a fundamental question: How do we move from raw observation to meaningful interpretation in modern research? His answer traced the entire research lifecycle, positioning openness, interoperability, and transparency as essential ingredients. Drawing on studies that show how different choices in data preparation lead to drastically different results, Lahti made a compelling case for shared standards and methodological clarity.

His overarching argument: bridging data science and research data management is not merely technical, it is epistemic. It requires both communities to adopt shared infrastructures, shared educational foundations, and shared norms that elevate transparency as a scientific value.

The Human Infrastructure of Data (Daphne Raban)

Daphne Raban shifted the lens to data stewardship which she called a “bridge profession” sitting at the intersection of technology, governance, and human judgment. As data volumes grow and automated tools proliferate, she reminded us that stewardship is what keeps data meaningful, contextualized, and ethically sound.

Raban illustrated the diverse impact of stewards across healthcare, finance, government, and research institutions, grounding her argument in the data cycle perspective advanced through the Israeli national initiative on data science education. In her framing, stewardship is not just about compliance; it’s about building trustworthy, reusable data ecosystems sustained by communication, documentation, and collaboration.

Parallel Universes: Awareness Gaps in Data Education (Phil Bourne)

Phil Bourne then highlighted a striking and often overlooked fact: students in data science programs worldwide typically have no exposure to organizations like CODATA, RDA, or WDS. Meanwhile, those global data organizations often operate with limited awareness of the educational and research priorities of academic data science. These are, Bourne argued, parallel universes that urgently need bridges.

His proposed actions were concrete: connect student groups, align leadership networks, embed governance into data science curricula, and convene joint thematic workshops on AI, synthetic data, and data ethics. He framed data as a continuum – from production to engineering to analysis to societal impact – and argued that without collaboration across these steps, sustainability and trustworthiness will remain elusive.

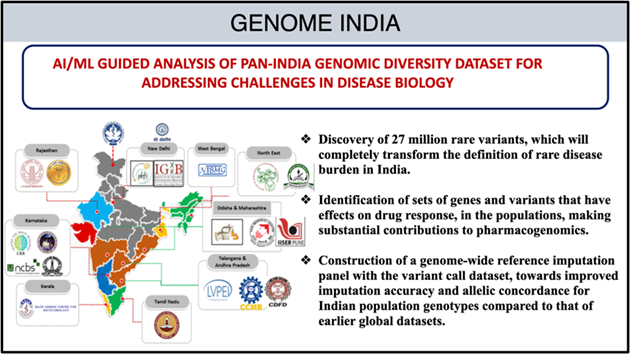

Data Literacy for Everyone: K–12 and Community College Pathways (Padmanabhan Seshaiyer)

Padmanabhan Seshaiyer expanded the conversation into the educational pipeline, urging the community not to wait until university to introduce data literacy. He showcased innovative K–12 and community college bridge programs that pair culturally relevant pedagogy with inquiry-based learning grounded in the Data Cycle.

Students move from no-code tools to higher-code environments, tackling authentic problems—from geometry-based triangulation tasks to investigations of social issues such as bullying and community safety. These programs embed ethics, design thinking, social justice, and civic reasoning alongside technical skills.

Seshaiyer’s message was clear: building an equitable data future requires early, inclusive, and context-aware data education.

Embedding FAIR into Australia’s Climate Modelling Software (Kelsey Druken)

Finally, Kelsey Druken offered a concrete case study of integrating data stewardship directly into infrastructure within Australia’s national climate modelling system, ACCESS. Climate modelling, she reminded the audience, is intensely data-rich, but native model outputs often lack documentation, standards, and consistent metadata. FAIR compliance tends to happen afterward, manually, and inconsistently.

ACCESS-NRI is now working to embed FAIR principles inside the software workflows themselves. By developing versioned data specifications, harmonized naming conventions, controlled vocabularies, and comprehensive metadata at the point of production, they aim to ensure that FAIR becomes the default, not the afterthought.

Druken’s work powerfully illustrates what it looks like when practice and infrastructure finally align—a challenge raised repeatedly throughout the panel.

Across these five talks, several themes emerged:

- Interoperability and transparency must be built into workflows—not bolted on later.

- Education is the shared foundation, from K–12 to graduate programs to professional development.

- Stewardship is central, not peripheral, to both science and data science.

- Organizational silos hinder progress across global and academic communities.

- A roadmap is needed, and the audience’s input will help shape one for future CODATA, RDA, and ADSA collaborations.

Possible next steps include forming a CODATA Task Group or RDA Interest Group, coordinating ecosystem tools and shared training resources, and proposing a companion session for the next ADSA meeting. Though there was not broad support for creating a new (interest or task) group, the people assembled were interested in further opportunities for continuing the conversation.

Amy Nurnberger (MIT), who attended the session, has already taken action following the IDW session. She and others have proposed a follow-on session at the upcoming Research Data Access and Preservation (RDAP) virtual conference to ensure the information science and library communities weigh in on bridging this divide.

The Future of Data Depends on Us Learning to Work Together

If there was one message that resonated across the session, it was this: No single community can build the data ecosystem and the community needed; it requires data stewards, data scientists, educators, and the infrastructure providers working together.

Bridging the gaps between these worlds is not simply a matter of efficiency or coordination. It is a matter of scientific integrity, ethical responsibility, and global impact.

The panel made clear that the future of data – open, FAIR, ethical, and societally meaningful – will be built only when we stop treating research data and data science as parallel tracks and instead recognize them as parts of a shared, interdependent community.

Co-organized by the

Co-organized by the  infrastructures can promote science and innovation in line with the SDGs.

infrastructures can promote science and innovation in line with the SDGs.