By Bylhah Mugotitsa, Agnes Kiragga, Steve Cygu and Miranda Barasa, African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC).

If there was ever a place where coffee, curiosity, and code met perfectly, it was International Data Week 2025 in Brisbane. You could feel the excitement from the minute you walked into the Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre, the kind of energy that tells you something important is happening here. It wasn’t just about machine learning models or the latest frameworks; it was about people, relations, and future collaboration. From early-morning panels on open science to late-afternoon debates on ethical AI, every conversation carried the same heartbeat: data is no longer the property of machines; it is the language of humanity.

In our presentations and panel discussions by African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) (Agnes Kiragga’s exploration of building sustainable data science ecosystems in Africa, Miranda Barasa’s insights on co-designing data infrastructures for collaborative research through the Data Science Without Borders (DSWB),

In our presentations and panel discussions by African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) (Agnes Kiragga’s exploration of building sustainable data science ecosystems in Africa, Miranda Barasa’s insights on co-designing data infrastructures for collaborative research through the Data Science Without Borders (DSWB),  and Mugotitsa Bylhah’s reflections on longitudinal data harmonization and integration under the INSPIRE Mental Health project), we found ourselves returning to a shared conviction: data must always return home. It must speak back to the communities it comes from, in language they understand, so that it can truly serve.

and Mugotitsa Bylhah’s reflections on longitudinal data harmonization and integration under the INSPIRE Mental Health project), we found ourselves returning to a shared conviction: data must always return home. It must speak back to the communities it comes from, in language they understand, so that it can truly serve.

The Philosophy of Data in a Changing World

Philosophers have long said that progress begins with understanding ourselves. In today’s world, that self-understanding is captured through data. Yet, as the Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye once said, “Knowledge must carry moral weight. It must serve community.” That is what Africa’s data movement is slowly but surely coming to embody: the moral dimension of measurement. From Nairobi to Dakar, Lusaka to Kampala, we are learning that data is not just about precision. It is about people, policy, and purpose. In Africa, we now promote data innovations developed by Africans, using African datasets and the broader African community.

Philosophers have long said that progress begins with understanding ourselves. In today’s world, that self-understanding is captured through data. Yet, as the Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye once said, “Knowledge must carry moral weight. It must serve community.” That is what Africa’s data movement is slowly but surely coming to embody: the moral dimension of measurement. From Nairobi to Dakar, Lusaka to Kampala, we are learning that data is not just about precision. It is about people, policy, and purpose. In Africa, we now promote data innovations developed by Africans, using African datasets and the broader African community.

At IDW2025, the sense of connection was real. Everyone seemed to recognize that the next chapter of data science will not be written in isolation. The conversations around “data without borders” were not just technical. It was about the idea that collaboration should transcend institutions, countries, and disciplines, allowing knowledge to move freely and ethically where it can do the most good. This aligned well with the purpose of the APHRC’s Data Science Without Borders Project (DSWB).

Our Work at APHRC: Building Cohesion Out of Complexity

In our session on ‘Operationalizing Ethical Data Governance in Africa: Applying CARE Principles and Developing of Data Sharing Agreements in African Institutions’, we shared how the INSPIRE Mental Health Initiative at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) is harmonizing longitudinal health data across multiple African Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) sites. Using frameworks like the OMOP Common Data Model and DDI-Lifecycle metadata, we are building bridges across diverse datasets, from clinical notes to community surveys, to make them comparable, reusable, and meaningful for policymakers.

We also discussed some of the key challenges from early data mapping like inconsistent data quality checks and how proper investment in digital infrastructure and training can drive AI innovation. Yet, with AI increasingly shaping health, governance and economic systems across Africa, the need for conversations around context-appropriate AI governance frameworks emerges. It is painfully obvious that Africa simply importing models built elsewhere is not working, instead homegrown approaches grounded in local realities and societal norms are what is needed. Collaborative initiatives like DSWB show the potential of AI becoming a catalyst for inclusive, sustainable development when African institutions co-design solutions grounded in shared governance and ethical use.

Our DSWB project aims to build a new generation of African data scientists who can work collaboratively across borders, sharing tools, models, and ideas while respecting the sovereignty and privacy of national datasets. It’s a space where African researchers from Kenya, Uganda, Senegal, and South Africa come together to co-create solutions that work for their communities. Through DSWB, we have begun exploring federated learning, an approach that allows models to be trained across multiple datasets without moving sensitive data. This is a quiet revolution in the making. It means we can collaborate globally while keeping data local and secure -and maintaining data sovereignty.

Beyond the Numbers: The Human Moment

What made IDW 2025 truly special was both the advancements in data technology but also the people. The hallway chats, the coffee-break laughter, and the sense of shared curiosity were as valuable as any keynote. We found ourselves among a community that understood both the rigor and the heart behind the numbers. These moments reminded us that behind all the servers, scripts, and dashboards, the data community is really a people community. We might speak in lines of code, but what connects us is a simple truth: we care about the same world.

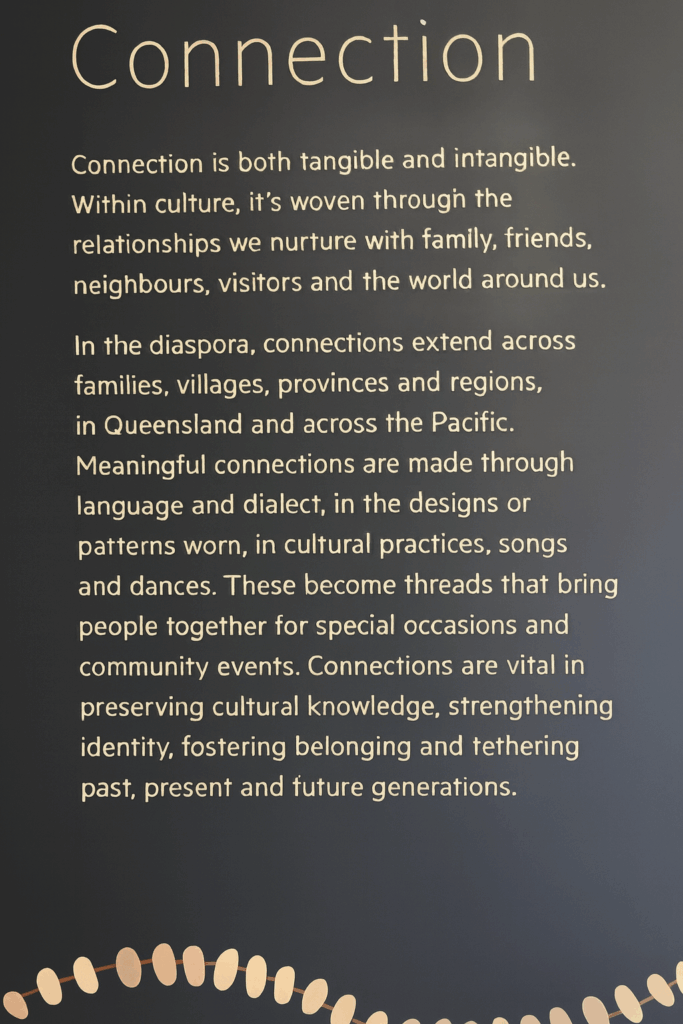

And then there were the lighter, unforgettable moments, the kind that conferences rarely put on the agenda but everyone remembers. One evening, we hopped onto the CityCat ferry for a boat ride down the Brisbane River to an event at Eat Street Northshore. By the time we docked, the air was filled with music, laughter, and the irresistible scent of global cuisines. Somewhere between sampling Thai noodles, Ethiopian coffee, and Australian doughnuts, the serious talk of algorithms gave way to dancing!!

There was something about those small, human moments that made Brisbane feel like home. IDW2025 reminded us that being “home away from home” doesn’t always mean missing where you came from; sometimes, it means discovering that belonging can happen anywhere people share purpose, curiosity, and good humor. For a few days, we weren’t just researchers and programmers; we were a floating global village of storytellers, dancers, and friends who just happened to love data.

Looking Ahead

As we return from Brisbane, the invitation is clear: It is important to strengthen the pipelines we have established, engage in meaningful engagement with communities before publicizing our findings, and take action based on our discoveries.

Preparations are now underway for the next IDW, which will take place in South Africa, where we hope to enhance debates with an even bigger representation of African voices, develop cross-institutional collaboration, and increase our impact.

In the end, what we carried home from IDW2025 was that in a world often divided by borders, data has given us a new kind of unity. A reminder that the pursuit of knowledge, when done ethically and inclusively, is a global act of humanity.

And that, perhaps, is the greatest lesson we carried home from Brisbane!!

Co-organized by the

Co-organized by the  infrastructures can promote science and innovation in line with the SDGs.

infrastructures can promote science and innovation in line with the SDGs.